How to Learn a Language

As the class coordinator of our school in Austin, I’m usually the first point of contact for potential students who want to know how to learn a language. In particular, how to learn Spanish. Naturally, I get the usual questions about our teaching methods and what we’re going to cover. Those questions have simple answers.

The most common question of all, however, is not so easy to answer: “How long is this going to take?”

This question comes in several different ways:

• When will I be fluent?

• How long before I can have conversations in Spanish?

• When will I understand the Spanish play-by-play in a soccer match?

I never reply to these questions with a definitive answer. And I never make any predictions about a student’s future progress. It’s not because I don’t want the burden of fulfilling the promise. But rather, it’s because the progress of a student, for the most part, depends on the student and not on the teacher. Bottom line; I can’t predict whether or not a student will put in the effort to learn a language.

This may come as a surprise to those who’ve never taught or learned a second language. The usual assumption is that a student is guaranteed to make steady progress so long as he / she has a good teacher. But that assumption, unfortunately, just isn’t true.

In my role, I’ve matched excellent teachers with students who made no real progress. And I’ve also seen students who thrived in their lessons in spite of having an average teacher. All these experiences point to the same undeniable conclusion;

The language progress of a student depends a lot more on the student than the teacher.

How to Learn a Language

With that in mind, it’s worthwhile for anyone who wishes to be fluent to understand – from a teacher’s perspective – how to learn a language. If progress is mostly based on the actions of the student, then what exactly are those actions? In this post, I’ll break down the 5 stages of learning a language and explain why the 4th step is the most critical of them all.

1. Introduction / Exposure

There’s nothing fancy about the beginning of the language learning process. Every teacher has his or her own style. But the routine of most teachers is to introduce basic verbs, vocabulary and phrases to the student. The student then repeats the words and attempts to use them in little conversational fragments.

Before the lesson, these new words were totally foreign to the student. They had never heard them before or never knew what they meant. But now that the teacher has emphasized them in a lesson, a big first step towards familiarity has been taken.

Look at it this way; a husband and wife could be married for 50 years and know everything about each other. They even finish each other’s sentences. But before their 50 years together and before any of that familiarity could happen, they first had to meet each other. Someone had to introduce them. That was their starting point. And now they’re fluent in each other.

Similarly, this exposure to new words is the starting point of learning a new language. You had never heard those words before but now you have. This is the equivalent of learning to crawl before you can run. Before you can discuss philosophy in Spanish or argue politics in Spanish, you must first learn to say “Hola” and “Buenos días.”

2. Learning / Accepting

I’ve worked with Spanish teachers whose lessons were 90% English and some whose lessons included zero English (full immersion). And before you assume that one of those styles is better than the other, I’ll just mention that I’ve seen students make effective progress with both styles and every style in-between.

But regardless of the style of a teacher, her responsibility at this point is to reconcile the two languages in the mind of her student. One way or another…with lots of explanation in English or with conversational Spanish, she must help the student to understand that this phrase in the new language is the way to express this phrase in his current language.

Sometimes, it’s a simple, word-for-word translation;

“¿Dónde está el baño?”

“Where is the bathroom?“

Other times, the literal translation doesn’t make any sense at all;

“¿Se me olvidaron las llaves.”

“The keys forgot themselves from me.“

Wait, what???

Analytical learners (like myself) often struggle when a translation doesn’t make sense. I remember one student, an engineer from India, who asked me this question;

How is it that “where” and “there” look and sound so similar in English, but “dónde” (where) and “allí” (there) don’t look or sound anything alike in Spanish?

He literally asked me that…and he seriously wanted an answer. With much sincerity, I explained to him that Spanish is not coded English.

Ask “how,” not “why”

The question of why the two languages are so dissimilar might lead to a interesting conversation. But those types of discussions don’t usually help students to make progress. Nearly every question from a student that begins with why can and should be answered with “because that’s just the way it is.”

The better question…the smarter question…is the one that starts with how. How do I say this? How do I say that? Whether it makes sense in your mind or not, learning the correct way to express yourself is the only thing that matters.

I like it It pleases me

In several languages such as French, Romanian, Italian and Spanish, to say that you like something, you basically need to express that it pleases you. The object is doing something to you (pleasing) rather than you doing something to it (liking). The sooner you understand and accept that “liking” is expressed with “pleasing” in these other languages, the sooner you’ll move on to the next concept.

In Spanish, saber and conocer both mean “to know,” but not in the same way. We saber facts and information but we conocer people and places. That’s simple enough and that’s really all there is to it. Just accept that knowing is expressed with two different verbs and move on.

This stage is simply an attempt to get a theoretical grasp of how new words, verbs and phrases are used. As soon as these “rules” are clear in the mind of a student, he will then understand those words and phrases when he hears them. And of course, he will more accurately use them to express himself.

3. Practice / Exercise

Just like stages 1 and 2, stage 3 occurs in the classroom. Also, all 3 of these first stages are the responsibility of the teacher. It’s the teacher who creates the lessons and decides which words to introduce to the student (stage 1). It’s the teacher who explains how those words are used (stage 2). And it’s the teacher who comes up with little exercises and mini-conversations which help the student to practice those words (stage 3).

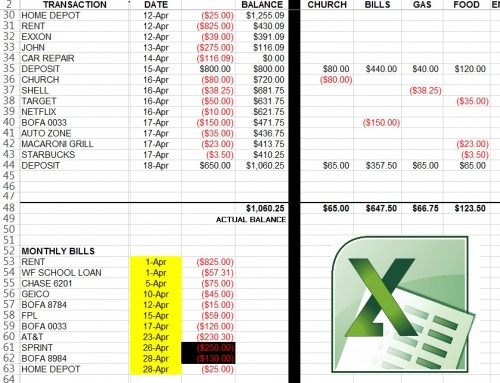

Most language textbooks are loaded with these exercises. They’re fun and challenging. They ensure that a student truly grasps the rules that he learned in stage 2. While learning Latin-based languages, half of this time is used to practice verb conjugations. Verbs have several variations…depending on who’s doing the action of the verb (me, you, us, someone else) and when they did it (past, present, future, etc). These variations are called conjugations.

Conjugations are relatively simple in English. Regardless of who spoke and regardless of when they spoke, there are only a handful of conjugations to express this verb in English; speak, speaks, spoke, spoken and speaking. That’s it, just five.

In Spanish, there are five or six conjugations of hablar (to speak) in the present tense alone. And then another six in the past tense. And another six in the other past tense. With each tense carrying six distinct conjugations, you end up with dozens of ways to express one verb. Meanwhile, in English, a grand total of five. English is hard to learn for a number of reasons, but its verb conjugations are not one of them.

Conversational Practice

The big advantage of learning in a class setting is the opportunity to try and use the new language with others. By engaging in several contrived conversations with the teacher and other students, you establish a critical confidence that your understanding and your expressions of the language are accurate and good.

Language books and software don’t facilitate this confidence. Languages are inherently social, which means they’re meant to be learned from and with other people. Textbooks and language apps are excellent for stage 2. But their effectiveness at the practice stage is limited because…you know…they’re not people. They can’t diagnose the errors you’re making nor offer a quick correction…at least, not yet. The most important aspect of the practice and exercises of a class setting is that it trains a student for stage 4.

4. Application

Stage 4 creates fluent students. This is the stage where the real progress takes place, but it’s the most under-emphasized stage of the five. The best language teachers are not the ones who write the best lessons, nor the ones with the best explanations of grammar. The best teachers are those who train their students to apply the language between classes.

Before explaining what it means for a student to apply a new language to his daily life, let’s clarify what it doesn’t mean. Application of a foreign language is not the occasional chat with native speakers of that language. Attempting to use your new language skills in social settings is actually stage 5; Real Conversations.

Chatting with native speakers is fun and exciting. That’s the big goal, isn’t it? Understanding them and being understood by them was the motive for taking classes in the first place, wasn’t it?

Yes, that’s right. But let me emphasize here that the title of this post is How to Learn a Language, not How to Use a Language. If you have a social outlet or a workplace setting where you can use your language skills with others, awesome! Yes, that’s the goal and that will always be the goal.

Daily application of the language, however, is the stage of learning which best prepares you for those conversations.

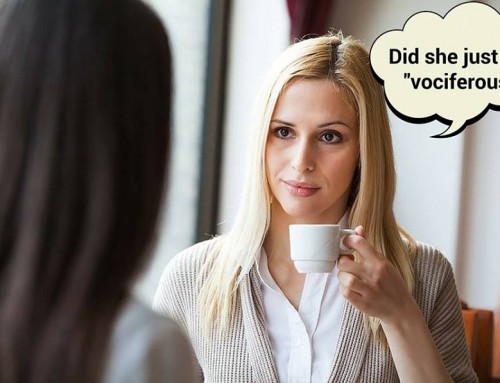

To apply a language is to purposely vocalize thoughts and actions during your daily routine.

That’s it. Whatever it is you’re doing, you should be explaining every detail – out loud – in the foreign language that you’re learning. It doesn’t matter if anyone else is listening. In fact, it’s going to be easier for you if no one’s listening. This not only applies to your actions, but also to your thoughts. Whatever comes to mind, try to say it.

To get my Spanish-learning students in the habit of doing this, I often have them explain everything that’s happening around us. In a public place, I ask them to talk about the people who are coming and going. I ask about every detail of their transaction at the register. Sometimes they speak too generally. For example:

El barista me dio la taza de café.

The barista gave me the cup of coffee.

…so I ask them for details:

¿Cuánta leche puso en tu café?

How much milk did he put in your coffee?

¿Cómo pagaste?

How did you pay?

¿Si el total fue $6.50 y le diste $10, cuánto cambio te dio?

If the total was $6.50 and you gave him $10, how much change did he give you?

¿Esa chica en aquella mesa…qué está haciendo?

That girl at the table over there…what is she doing?

I can go on and on with these questions indefinitely because every answer leads to more questions.

There simply isn’t enough time in the classroom for all the speaking and thinking in the new language which needs to happen. The student must take it home with him and practice on his own. After completing this post, I’ll write another post which goes into detail about the process of applying a new language. It’s a very proactive, purposeful approach to learning. There’s nothing “natural” or “casual” about it. It’s a full-scale “self-immersion” which isn’t dependent on rare opportunities to chat with native speakers.

5. Real Conversations

Consider yourself lucky if you have a group of native speakers who will patiently chat with you in the language you’re trying to learn. Last time I checked, most people have limited patience for those who don’t already speak their language.

As I mentioned earlier, having real conversations in the target language is always the goal. To the extent that you can do it, DO IT! Join a group of people who speak that language and simply listen to them talk. Contribute to the conversation as often as you can. It’s so rewarding when the doors of new cultures are opened up to you through language.

But don’t be surprised or discouraged if these conversations become frustrating. They’re speaking to each other at Level 10 and maybe slowing it down to Level 7 when they talk to you. But if you’re still at Levels 1-4, it’s going to be more frustrating than rewarding.

This is why you cannot depend on occasional conversations to deepen your skills in the language. It’s unstructured, unpredictable and infrequent. A student who is casually learning a language with this social approach will eventually lag far behind the student who methodically applies the language to his daily life. That is why the 4th stage of Application is the language-learning step that we emphasize the most.

Those who make real progress towards their language-learning goals are those who fall in love with the process. Those who don’t have a real incentive to learn a language will eventually fall away…and that’s ok. In another post titled Maybe You Shouldn’t Learn Another Language, I explain that language learning isn’t for everyone.

But if you truly do have bilingual aspirations, these 5 stages are the way to make it happen. It cycles over and over again. When advanced students hear a new word or phrase, they must process it from Stage 1 to 5 in order to become fluent in that word. The process never ends.

Another good article about language acquistion on Babbel.com: 10 Tips To Learn Any Language From An Expert